Coming up for air | A Recollection of an Election (and death)

Tuesday, November 4, 2014 at 09:59PM

Tuesday, November 4, 2014 at 09:59PM On an election’s eve about 12 years ago, I was sitting on the floor in a worker’s union building. I can’t remember which union it was, but they’d lent their space to the 2002 Democratic Coordinated Campaign.

There were many reasons why I was on the floor. I hadn’t slept in two days. I was working three jobs. My wife and I had quit our careers, gotten married, moved to a different city and bought a house. That all took place in a month.

And our guy for US Senate was down in the polls. He’s what they call in the biz “a good candidate.” He’s tall, handsome in an 80s Magnum PI sort of way, and he belongs to a major law firm. But the week prior he’d talked himself into a hole on national TV. I remember watching and believing he could pull it off, but every word that spilled out of him fell deeper into a well of confusion. It was as if he’d lost control of his mouth. He was stuck trying to explain the three legs of America’s financial stability. He’d gotten out two, but struggled to convey the third. With is hands he gestured what looked to be the shape of a leg, maybe one that belonged to a short stool. Accompanying the pantomime was a smattering of adjectives, none of them really wanting to be together. It was hard to watch.

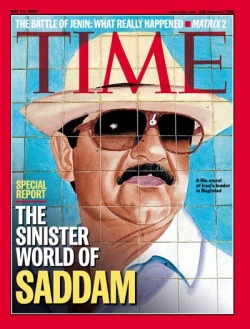

A few days later I would be talking to voters and one guy would say, “You’ve got balls. Didn’t you see him on 2002 was bad year to not want to attack Iraq. Meet the Press?” I tried to focus on the compliment part of it.

2002 was bad year to not want to attack Iraq. Meet the Press?” I tried to focus on the compliment part of it.

But I wasn’t sitting on the floor of the union building because of my little mortgage problem. I was on the floor because I could no longer physically stand. It would have been the best time in my life to be drunk, but I didn’t have time for it. I was high on something else, if you can call it that. What I didn’t know was that I was being killed by carbon monoxide.

You always hear how people go to sleep and simply slip away. They have a headache but it’s been a stressful day so they do what anyone would want to do: they crash. I had the benefit of being a “Volunteer Coordinator” for hundreds of people who in a few hours were going to fill the very hall in which I sat alone. This meant there was no sleeping until all the preparations were done. Elections don’t leave time for dying.

And let me just say this about working for a campaign. It starts as just a job, or as something you’ll just dabble in a bit. But soon you’ve forsaken sex and food for knocking on a stranger’s door. You start to believe the rhetoric and, despite two hundred-plus years proving the opposite, believe that one person can feed the poor and make your nipples shoot Slim Jims. You really have no choice. If for one second you doubt the momentum, you’ll fall off the treadmill and get trampled by five hundred people with Blackberries. Every third day or so, just when you think you can’t tolerate another drop of coffee, someone you barely know tells you if you stick it out there will “be a spot on his staff.” Rarely is that positive, but in politics staff spots are offered in lieu of money, and reality. Because he has to be elected first, and that’s why you must work harder. And you’re off again, swilling caffeine and surrounded by doers and shakers and suspicious, fat men who buy you beers and swear one day you’ll go somewhere. Plus there’s media involved, and a spitting, blowing maelstrom of rumors and mud. When you’re in the middle, in the huddle of camaraderie and like-minded hugs, you don’t want to get out. So on some Saturday, when a boatload of hot, wealthy yoga moms are taking three hours to help you litter the town with your candidate’s picture, and you’re the frontman for a bevy of beautiful college kids all fresh faced and ready to devour your carcass, you soldier on.

On this day, my college kids weren’t so hungry anymore. Four young go-getters helped stuff fliers into bags and call potential voters. We were a good team until I found two of the three females lying on the floor.

“What’s the matter?” I growled in a funny bear voice, trying to make my disappointment sound more like friendly sarcasm.

They had headaches. They were dizzy.

I told them to eat something and drink some water. They said they had. I was about to implore the third woman to motivate her friends, until I found her slumped over a desk.

“Are you sick?” I delivered with ice.

She nodded and got up. She and her friends were going to go home she said. I couldn’t believe it. They helped each other up and walked out. I turned and rolled my eyes at Brian, the one other guy. He tried to match my incredulity, but was busy crying.

To be fair, he wasn’t Steel Magnolias weeping, but his eyes were watery and red. He worked a little bit longer, but things weren’t going his way. He’d roll up an informational piece and, while reaching for a rubber band, would let it unroll. Then he’d drop the rubber band while trying to roll up the sheet again. Finally, he gave up and approached me. He kept walking until all the personal space was gone. A few inches from my face he blinked some tears and talked in slow motion about needing to leave.

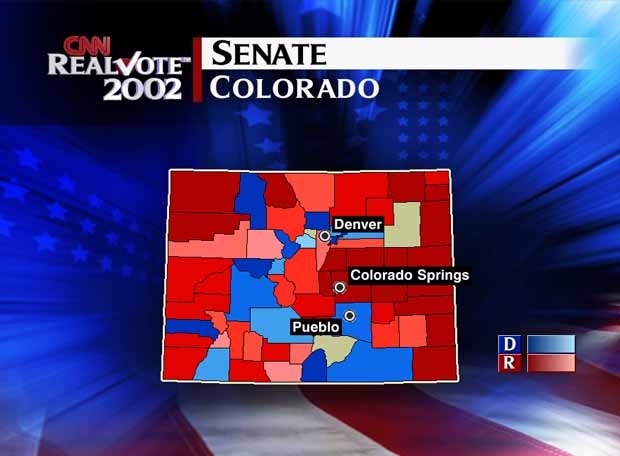

And here's an image of our brains shutting down.

And here's an image of our brains shutting down.

I kind of took on a martyr role. I told him it was fine. I’d manage to get everything done. I stormed around the office, drinking bottle after bottle of water. I’m usually a thirsty guy, but now I was going to wash away my pain. And then, at some point, I sat down and started thinking about everybody going home. The two girls who were the first to get sick were petite. And the third was just as thin but taller. Brian was bigger, but at least eighty pounds lighter than me. I wondered if we all had the same thing, but because I was the thickest of the group, it was taking me longer to succumb. At some point my being dense would be an advantage. And then I crawled outside.

In kind of an industrial rainbow, the bright florescent of the union hall streaked into the dim yellow of the street. I would have a hard time dialing 911. I got to my knees and took a deep breath of outside air. I closed one eye, and focused on the numbers. I wobbled. If I were to die, my final act would be drunk dialing emergency services.

Other than growing up in a wood-heated home where breathing smoke at least meant you were warm, I had never had any experience with carbon monoxide poisoning. It wasn’t until the firefighters hoisted me into the truck that I realized how lucky I was to be alive. It helped that one of them actually said, “You’re lucky to be alive.”

One of the guys walked around the room with a CO2 detector. It beeped rapidly and he agreed. It was off the charts. I spent the rest of the early morning leading an ambulance around the Denver metro area to find the other four. Turns out they all were OK, but Brian and I had to spend a few hours in the hospital for oxygenating.

One of the firefighters said that the building’s exhaust had been blocked with a mound of old clothes. It was intentional, but I never heard any followup as to an investigation. However, I thought of our candidate baffling Tim Russert and the world by trying to finger draw furniture in the air, and I wondered if someone had done the same thing to his house.

That night, at the big election party, I got a little recognition. It was Tuesday and I hadn’t slept since Sunday. My wife was getting to spend some quality time with a sleepless prick at a depressing event for a losing candidate. On his way to his concession speech, our Senatorial hope stopped and pointed at me. He leaned my way and shouted against the noise, “I lost but you’re still alive.”

I’m pretty sure it wasn’t spite. Like “oh god, not both!” I didn’t want to ask him to try and explain. It was simple, it was true, and it was as right as any politician had ever been.

Reader Comments